Imagine mastering those everyday tasks with the magic of assistive technology…

Hi, I’m Laura, and as a Therapy Assistant in the Barnsley Assistive Technology Team (BATT) and Occupational Therapy apprentice at Huddersfield University, I witness those AHA! moments every day.

This blog post discusses how less really can be more, by describing two clients who unlocked success with the humble switch instead of ‘high-tech’ alternatives. Please note that pseudonyms have been used to protect confidentiality and links have been provided for further information on potentially unfamiliar terms, such as ‘access method’, ‘switch’, and ‘environmental controls’ (EC).

At the end of last year, I was asked to give a short presentation on my role to include some client stories that showed my involvement throughout the assessment process. Now, I had only been in the team approximately 4 months at this point, and public speaking has never been my strong point! Although, presenting on teams alleviated some of these nerves, and I was keen to show what I had been up to since joining the service along with how I could support clinicians and clients in future assessments.

I chose two clients that I had been working with who differed in age, diagnoses, goals, and of course, personality. My aim had been to give a range in all areas, however, what I hadn’t realised at the time of preparing for this presentation was that both of these clients actually had one thing in common: they had both began their journey with assistive technology as users of more complex access methods, and had both found that what suited them the most was the humble switch.

Client one:

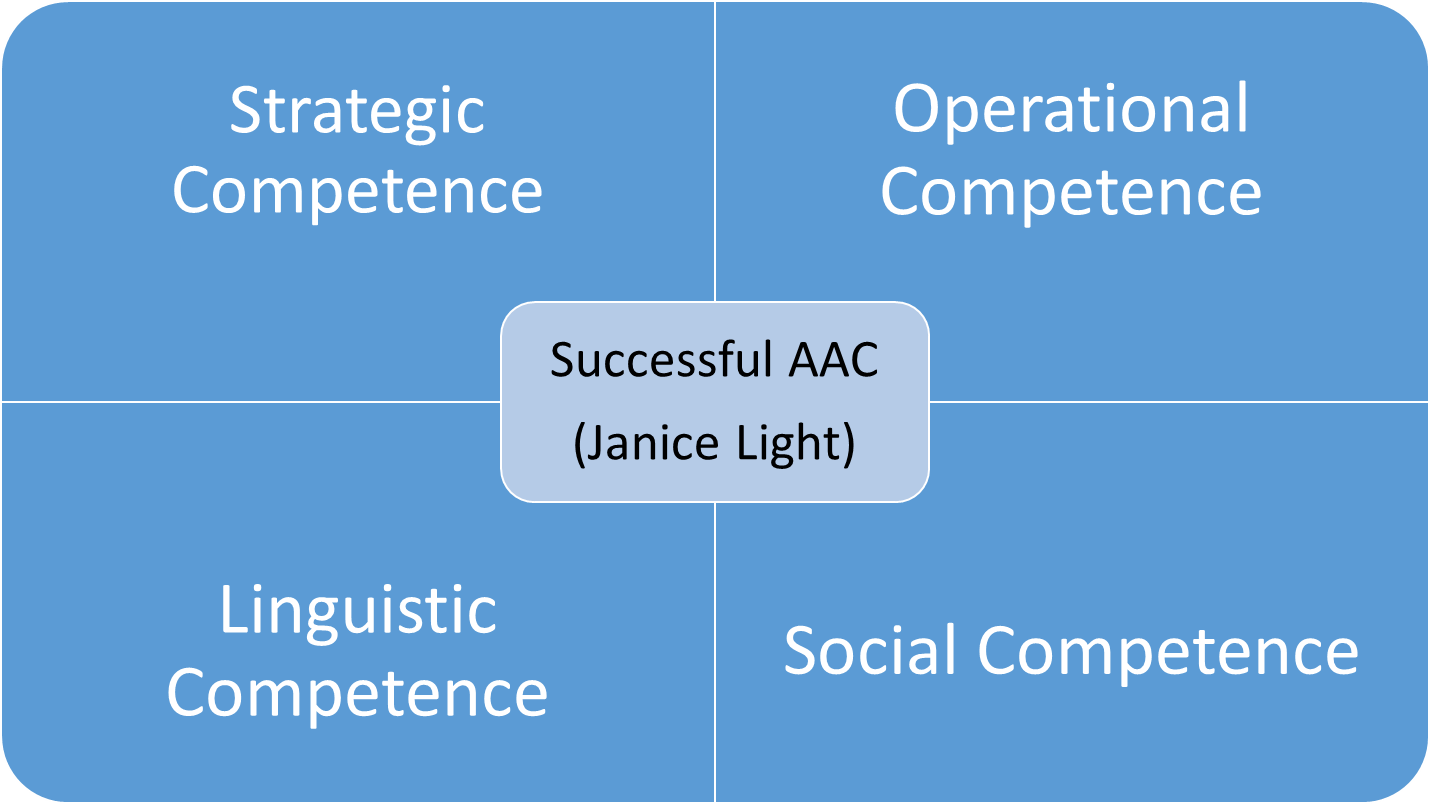

Ashley is 50 years old and has a diagnosis of Cerebral Palsy and a mild learning disability. Ashley was referred to BATT for an AAC assessment, as their main communication method was speech, but this was often unintelligible, especially to those who don’t know them. Ashley also used a range of gestures and facial expressions to communicate, but often became frustrated when misunderstood and found mending communication breakdowns extremely difficult. Ashley lives in an apartment in an assisted living complex with frequent carer visits, and is an electric wheelchair with joystick control user.

Ashley was assessed by a BATT Specialist Speech and Language Therapist (SLT). The initial outcome of the assessment was to trial a Grid Pad with a symbol-based vocabulary and a joystick as the access method, as this was something Ashley was familiar using. I became involved at this point to support the trial period and assist Ashley in both learning the vocabulary and practicing the joystick control. Ashley proved to be a very competent joystick user, however, Ashley’s motivation and engagement in the support sessions I was providing decreased over time. Following a conversation with the clinician, we identified an exciting possibility: introducing Ashley to BATT’s Service User Representative whose integrated joystick system, controlling both communication and mobility, could have been just what Ashley needed. We were all excited to see if it sparked a connection, so we arranged a meeting for Ashley to see this first-hand.

The meeting was a great success and Ashley was very receptive to witnessing another AAC user’s demonstration of how they navigate their device and swapped between controlling their chair or communication aid using a joystick and a single switch. However, Ashley let us know that due to shoulder pain Ashley did not want to use the communication aid in this, which explained the reduction in motivation. Instead of the joystick, the Service User Representative proposed switch scanning and showcased their foot switch and row-scanning setup. Ashley showed immediate interest in this alternative method, and eagerly agreed to trial a switch in place of a joystick.

At this point in my presentation, a really valuable discussion was had with the team wondering if this suggestion had additional value coming from an AAC user, rather than myself or the clinician. I would argue that it did, as it added an authenticity and element of lived experience that we could never offer. This appeared to inspire Ashley to continue a journey with AAC, and Ashley went on to trial switch access with new-found motivation and great success.

Client two:

Sam is 70-years-old and has a high spinal cord injury, which resulted in Tetraplegia with limited right upper limb movement. Sam lives in a nursing home and had goals that were EC based, including TV controls, bed controls, and accessing various apps on an iPad.

Sam was assessed by a BATT Specialist Occupational Therapist (OT). The outcome of the assessment was to trial using voice control on Sam’s personal iPad with a HouseMate transmitter and app. This proved to be very successful during the initial assessment, and the clinician requested that I provide some support sessions to assist Sam in learning the commands and navigation of the system. These support sessions proceeded with varying success. Sam’s voice was found to vary in its reliability, often being affected by fluctuating levels of fatigue and wellbeing. Sam also found remembering specific commands to be difficult and tiring, often becoming frustrated if the device did not respond. I fed this back to the clinician and we arranged a joint visit with Sam.

During this visit we presented switch scanning as an alternative, and Sam took to this right away. Sam responded well to the visual aspect of following the highlighted cells, and was very successful with the timing of scanning. It transpired that speed was not a priority for Sam, and accuracy along with reduced cognitive load were more important, as Sam often experienced periods of fatigue but would still want to be able to use the device. Sam went on to achieve all of the EC goals using single switch access, and was very grateful for the change this has made to their independence.

Reflections

One might wonder why switch access was not the first option that was considered for these clients. Following my presentation, multiple clinicians reflected that they can sometimes discount switches in the beginning of an assessment in favour of ‘faster’ options. They acknowledged here however that, as in the case of Sam, this might not be as important to some clients as we may assume. One clinician suggested that for some AAC users, speed of communication may be a goal expressed by their regular communication partners rather than the client themselves, which perhaps highlights a need for raising awareness on the importance of patience and understanding, rather than focusing on the quickest method of access. Furthermore, the allure of “cutting-edge” technology, such as Eyegaze, can overshadow the effectiveness of switches, leading clients to underestimate their value.

During this discussion, it became apparent that the switch can sometimes be unappreciated and overlooked, despite its significant strengths, such as ease of use, the minimal physical ability required, and availability of visual and auditory prompts. However, it is important to note that the switch is not suitable for every client, as it can be considered cognitively demanding in terms of attention and timing, slow, and inefficient in comparison to other methods.

Ashley and Sam were both heavily involved in the decision-making process during their assistive technology assessments. In each case, the clinician took a client-centred approach that ultimately prevented any risk of unintentional bias towards more ‘high tech’ systems, and led to the provision of the most appropriate access method for each individual in their current context – the humble switch.

You must be logged in to post a comment.